For the very latest superlight 7.3kg Brompton, see A to B 119!

For the very latest superlight 7.3kg Brompton, see A to B 119!

The FULL ARTICLE on the 2005 bike can be downloaded in A to B 49 for just 99p here!

Big strong men sometimes ask us why we put such an emphasis on reducing the weight of folding bikes. If you have to ask the question, you really don’t need to know the answer.Taking weight out of a bicycle has little effect on performance, but a great deal of effect on the ease with which it can be carried.

Many people would be willing to use a folding bike but cannot lift a 14kg (33lb) weight, let alone haul it upstairs or run for a train with it. Get the weight down to a reasonable 12kg, and most people can deal with it. At 10kg, we’re up to, perhaps, 90% of the adult population, and if weight can be pared down to less than 8kg (already feasible, but expensive), the bike becomes practical for almost anyone to carry.Weight reduction is a truly emancipating technology, bringing folding bikes to those previously excluded with respective to the action ac.You might argue that they still need to be pretty wealthy, but this is really only a state of mind problem. If a high-end folding bike eliminates the need for a second or third family car, a purchase price of £1,000 or so can represent great value for money.This technology is getting less expensive, but don’t expect fanciful titanium creations to ever be cheap.

Design Challenge

The challenge for designers is to get as close as possible to the 8kg weight goal without seriously compromising the strength and rideability of the machine. Current leader is Dahon, whose Helios SL weighed a genuine 8.65kg (19lb) when we tried it in August 2004.The Helios SL is a delightful machine, but it has 20-inch wheels, so it makes quite a big folded package. It also comes with beautiful, but frail Rolf wheels, and no mudguards, so it’s not really a daily commuter machine.

The Brompton is a classic commuter bike, but it’s heavy. In A to B 1, we built a lightweight Brompton weighing 10.9kg. Considering that the Brompton weighed 12kg at the time, this was, with hindsight, quite a good result for a broadly conventional three- speed bike.The following year we were at it again, fitting a 1950s alloy shell to the hub (saving a whacking 120g), fewer, slimmer spokes, a carbon fibre seat pillar, Birdy suspension polymer and a few other bits, hauling the weight down to 10.4kg (22.9lb).

Some lightweight parts are strikingly attractive in their own right.This is the TA AXIX Light bottom bracket

For the next few years, the bike clocked up several thousand miles. Most of the parts lasted well, the only weak spots being the aluminium rear roller securing bolts (they should have been titanium), and the carbon fibre seat pillar, which ate through two frame bushes and ended up dangerously worn itself. In the meantime, of course, the industry had been busy with its own weight reduction programme, and although some of the new stronger Brompton parts (such as the handlebars) were heavier, most were lighter…The company was gradually catching up.

In April 2005, Brompton launched the superlight 9.7kg S2L-X and left our lightweight machine looking a bit sad. Could we do better using the S2L’s new technology – principally a two-speed derailleur hub and titanium frame parts?

A to B Bites Back

Eight years after putting together our original machine (the day of the Princess of Wales’ funeral, for those interested in historical minutia), we’ve built a new machine that’s both lighter and stronger.This isn’t a stripped-down special – our bike has mudguards and all the usual equipment you would expect to find on a Brompton S2L-X, but with the ‘traditional’ M-type Brompton handlebars, because that’s the way we like ‘em. This older design has a shorter stem, saving 60g, but a more complicated handlebar, adding 110g, giving a net weight increase of 50g. Drat and double drat.The taller handlebars also make it impossible to fit the S-type’s shorter Jagwire cables, adding another 50g, so before we’ve even started, our bike weighs 100g more than Brompton’s super-light model.

…the trick is to replace steel parts with titanium… or aluminium…

If our bike is effectively a standard machine, how is the weight taken off? The trick is to work methodically through the machine, replacing steel parts with lighter alternatives. For safety-related bits, this generally means titanium, which is as strong as steel, but about 40% lighter. Less critical things can be replaced with aluminium – 65% lighter than steel, cheaper than titanium (not much in these specialist areas), but weaker, so it needs to be treated with care. Cosmetic things can be made in plastic, or omitted altogether, but ‘easy’ weight savings of this kind will be hard to achieve if the development engineers have already done a good job.

Tranz-X clamp – note the reversed nut and pin preventing the clamp from rotating

As in 1997, we’ve laid out a table indicating the cost-effectiveness of each change. Today, most of these lightweight parts are easily obtainable from Brompton dealers and other specialist outlets, so they’re cheaper than they were eight years ago. At anything up to £1 per gram saved, it’s still an expensive business, but to paraphrase the RSPCA, titanium is for life, and not just for Christmas. Once you’ve raided the piggy bank and fitted the bits, they can be transferred from bike to bike until your knees give out, and then passed down as family heirlooms.

If you’re in the market for the bigger, more expensive chunks of titanium, it’s generally cheaper to go for broke and buy one of Brompton’s own lightweight machines. As fitting is so complex, the two-speed derailleur probably comes into this category too. Even if you’re hoping to upgrade a near-new six-speed bike, it will be easier (and cheaper) to sell the old one and buy a new two-speed.

Top of the ‘worth doing’ list are things like pedals, handlebar grips and reflectors, lighter versions of which can be found quite cheaply.We chose to leave the wheel reflectors off altogether, but you may feel it’s not worth compromising safety for the sake of a few grams. Other parts, like alloy spoke nipples and lighter 14-gauge rear spokes, are cheap, but fitting can involve a great deal of labour, and the long-term strength of the bike will be slightly compromised.The superlight S-type’s Stelvio Light tyres and tubes come into this category too – they are lighter, but more vulnerable to punctures.

Some standard parts are hard to beat – for example, there’s very little to choose between 3/32” chains.We spent £26 and saved a paltry 16g by fitting a KMC X9 Gold chain which is, believe it or not, gold plated. Still, it goes very nicely with the exposed brazes on the Raw Lacquer frame. It’s difficult to beat the weight of the standard Brompton saddle too. On our original bike, we fitted a Terry Race Vanadium saddle weighing 227g.We were able to reuse it, which is fortunate, because it no longer seems to be available.The best we could find today was the Fizik Vitesse Twintech ladies saddle, weighing a claimed 230g and costing £60.This sort of upgrade could never be cost-effective, but saddles are a personal thing, and in the final analysis, a lightweight bike is a fashion statement. Like any other fashion statement it wouldn’t be complete without a few decadent touches.

Anything we’ve missed? The cables and brakes could be lighter, but it’s unlikely the weight and complication would be worthwhile. Otherwise, apart from odd nuts and bolts, we’ll probably have to wait for Brompton to introduce a titanium mainframe, which would save perhaps another kilogram.

On the Road

If you’re worried about the lack of gears, don’t be. Under most conditions, the two-speed derailleur performs much like a conventional three-speed Brompton.The bottom gear of 56″ can tackle hills of up to 12.5% (1:8) with a suitably enthusiastic rider, and the top gear of 74″ is adequate for most urban situations. If you can live with a slightly high pedal cadence, it’s OK on the open road too.As we’ve suggested elsewhere, it may be possible to change the 16-tooth sprocket for a 17-tooth (a 53″ gear) without any other work, and with a bit of titanium-bashing, an 18-tooth can be squeezed in, giving a bottom gear of 50″.That’s almost as low as first on the old three-speed, but a bit of a jump down from top gear, so we’ve left the gearing unchanged and will see how we get on.

In theory, the lightweight parts make next to no difference in terms of speed, but the lighter rotating bits improve acceleration, and they certainly make the bike feel livelier and sharper to ride.We can only say that our lightweight bike seems to accelerate well, and it’s a delight to ride. If it feels good, that’s all that really matters…

Carrying the bike is obviously a lot easier. It’s difficult to visualise how light it is, but try taking the wheels off a Brompton L3 and lifting it…

What does the bike actually weigh? Er, um, a bit of a dispute here. All the parts, old and new, passed over our traditional scales, so we’re quite certain that our bike weighs 2.5kg less than a standard M3L, or L3 as it used to be called. But according to our electronic scales, the finished bike weighs 9.5kg, which is two or three hundred grams more than we were expecting. Drat and double drat!

And how much did it cost? This is another tricky question, because the costs depend on how you do it.To upgrade an elderly Brompton would cost around £800, excluding the two-speed kit, which is not really cost-effective as an upgrade. If buying a new Brompton, the cheapest option is to start with the superlight M2L-X, which comes with most of the Brompton lightweight kit for £873. Adding the Stelvio tyres and the A to B bits and pieces would cost another £250 or so, and bring the weight down to 9.2kg or 9.5kg, depending whose scales you believe.

ENGINEERING NOTES

Not all these parts can be bought off the shelf. The locknut on the Tranz-x seatpost clamp has been turned down to fit inside the Brompton frame lug, with two pegs fitted at the other end to stop the clamp assembly rotating, effectively mimicking the action of the Brompton clamp.The Birdy yellow suspension polymer is a useful upgrade, especially for lighter riders, but needs some shaping to fit – ours is also drilled like an Emmenthal cheese to give a softer ride. We used an aluminium bolt in the suspension, but this should really be titanium.The axle on the AXIX titanium bottom bracket has marginally less bias towards the chainring than the Brompton’s FAG axle. We fitted a 1mm shim, but tolerances vary – we probably didn’t need to. Two home-engineered bits we didn’t reuse this time were the alloy three-speed cable-guide nut (not needed) and the steering head alloy expander nut, which is now a standard fitting.

![]()

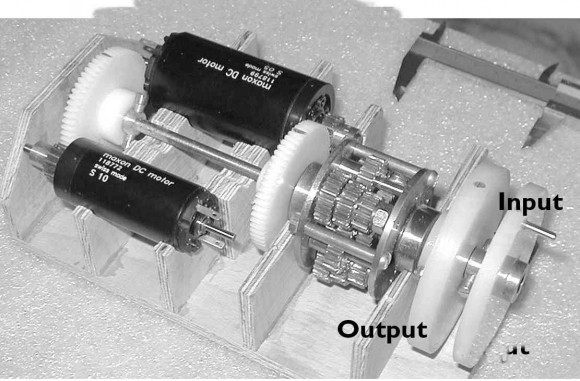

Cutting edge stuff! Whatever your preference in alternative transport, this issue will show you something entirely new. Folding bike? Follow our lightweight Brompton project – 10.9kg in 1997 and 9.5kg today. Electric bike? We can offer a range of 35 miles from a Lithium-ion battery… Gears? Professor Pivot investigates a practical fully automatic gearbox… Recumbents? Giant’s new Revive Spirit is stashed with technology.

Cutting edge stuff! Whatever your preference in alternative transport, this issue will show you something entirely new. Folding bike? Follow our lightweight Brompton project – 10.9kg in 1997 and 9.5kg today. Electric bike? We can offer a range of 35 miles from a Lithium-ion battery… Gears? Professor Pivot investigates a practical fully automatic gearbox… Recumbents? Giant’s new Revive Spirit is stashed with technology.

If you think about it, the quality of a child’s bike is really important. If a child grows up with a heavy, impractical bicycle, he or she starts life with the impression that bicycles are heavy impractical machines.The evidence from the current generation is that apart from dabbling with BMX, the vast majority stop riding bicycles just as soon as they can, and most never return. Rather disturbingly, there’s growing evidence that many in Alexander’s generation will never learn to ride at all.

If you think about it, the quality of a child’s bike is really important. If a child grows up with a heavy, impractical bicycle, he or she starts life with the impression that bicycles are heavy impractical machines.The evidence from the current generation is that apart from dabbling with BMX, the vast majority stop riding bicycles just as soon as they can, and most never return. Rather disturbingly, there’s growing evidence that many in Alexander’s generation will never learn to ride at all.

The Giant Revive, it’s fair to say, has been a long time coming.We first heard whispers of a commercially-produced semi-recumbent bicycle some years ago, and eventually saw one in the summer of 2002.The non-assisted versions went on sale the following spring, the electric variant finally arriving in the summer of 2005.

The Giant Revive, it’s fair to say, has been a long time coming.We first heard whispers of a commercially-produced semi-recumbent bicycle some years ago, and eventually saw one in the summer of 2002.The non-assisted versions went on sale the following spring, the electric variant finally arriving in the summer of 2005. A brief recap. In recumbent terms, the Revive might be described as a short wheelbase semi-recumbent.The frame is alloy throughout, with various bits hung from a solid- looking main tube that drops down from the steering head area, giving a usefully low step-thru, then sweeps back and up over the rear wheel.The wheel is fixed to another frame member that pivots just ahead of the crank and is supported by a spring/damper unit under the seat tube, which swings sharply upwards from the main frame.Wheels are 406mm (20-inch).

A brief recap. In recumbent terms, the Revive might be described as a short wheelbase semi-recumbent.The frame is alloy throughout, with various bits hung from a solid- looking main tube that drops down from the steering head area, giving a usefully low step-thru, then sweeps back and up over the rear wheel.The wheel is fixed to another frame member that pivots just ahead of the crank and is supported by a spring/damper unit under the seat tube, which swings sharply upwards from the main frame.Wheels are 406mm (20-inch). Less satisfactory is the weight, the price and the slightly awkward pedalling position. In its short life, the Revive has been produced in a number of versions, but only two models are currently on sale in the UK both with hub gears – Nexus 7-speed on the Revive DX N7 (£675), and Nexus 8-speed on the more luxurious LXC N8 (£875). Giant is a bit coy about weight, but reports suggest these non-assisted machines weigh at least 19kg (42lb), which compares rather badly with similar conventional bikes.With low drag and high weight, bikes of this kind tend to see more extremes of speed than a traditional bicycle – heart- stopping descents and painfully slow climbs. And that’s where the power-assisted Spirit comes in, because a little assistance goes a long way to even out your progress.

Less satisfactory is the weight, the price and the slightly awkward pedalling position. In its short life, the Revive has been produced in a number of versions, but only two models are currently on sale in the UK both with hub gears – Nexus 7-speed on the Revive DX N7 (£675), and Nexus 8-speed on the more luxurious LXC N8 (£875). Giant is a bit coy about weight, but reports suggest these non-assisted machines weigh at least 19kg (42lb), which compares rather badly with similar conventional bikes.With low drag and high weight, bikes of this kind tend to see more extremes of speed than a traditional bicycle – heart- stopping descents and painfully slow climbs. And that’s where the power-assisted Spirit comes in, because a little assistance goes a long way to even out your progress. At £1,499, the Spirit is the most expensive electric bike in the UK, by several hundred pounds. It’s also the most sophisticated: lithium-ion battery, integral trip computer, automatic halogen light and many other cumfy luxuries. Strangely enough, given the quality of the equipment, the Spirit is fitted with one of the world’s most basic hub gears; Shimano’s three-speed Nexus.We express surprise because this hub is also available in Auto-D form, and an automatic hub would seem ideal for a laid- back flagship like the Spirit. And this year, Shimano has introduced something called Di2 cyber Nexus, bringing together its generally well considered eight-speed hub with a front hub-powered computer, auto shift mechanism, auto suspension, auto lights, and… well, you get the idea.

At £1,499, the Spirit is the most expensive electric bike in the UK, by several hundred pounds. It’s also the most sophisticated: lithium-ion battery, integral trip computer, automatic halogen light and many other cumfy luxuries. Strangely enough, given the quality of the equipment, the Spirit is fitted with one of the world’s most basic hub gears; Shimano’s three-speed Nexus.We express surprise because this hub is also available in Auto-D form, and an automatic hub would seem ideal for a laid- back flagship like the Spirit. And this year, Shimano has introduced something called Di2 cyber Nexus, bringing together its generally well considered eight-speed hub with a front hub-powered computer, auto shift mechanism, auto suspension, auto lights, and… well, you get the idea.

Range on full power is so- so.There are three capacity lights: On our ‘mountain course’, the first popped off at four miles and the second at six miles, which almost caused us to abort the test. In practice, the gauge is a bit hit- and-miss, because we soon had two lights on again. Four miles on we were back with one, at 14 miles it began to flash, and the end came abruptly at 16.2 miles. Average speed was 13.7mph – quite low by modern electric bike standards, particularly considering the rapid descents. In flat country, we managed 17.4 miles at 14mph, which is even more disappointing.

Range on full power is so- so.There are three capacity lights: On our ‘mountain course’, the first popped off at four miles and the second at six miles, which almost caused us to abort the test. In practice, the gauge is a bit hit- and-miss, because we soon had two lights on again. Four miles on we were back with one, at 14 miles it began to flash, and the end came abruptly at 16.2 miles. Average speed was 13.7mph – quite low by modern electric bike standards, particularly considering the rapid descents. In flat country, we managed 17.4 miles at 14mph, which is even more disappointing.

Once upon a time, not so very long ago,if you lived beside a British trunk road your life would be a nightmare of congestion, pollution and constant danger. As the years passed, the nightmare spread; first to ‘A’ class roads, then ‘B’ roads (remember when you could cycle on those sweeping rural highways?), and finally to unclassified roads in all but the most remote corners of these islands.

Once upon a time, not so very long ago,if you lived beside a British trunk road your life would be a nightmare of congestion, pollution and constant danger. As the years passed, the nightmare spread; first to ‘A’ class roads, then ‘B’ roads (remember when you could cycle on those sweeping rural highways?), and finally to unclassified roads in all but the most remote corners of these islands. Not to put too fine a point on it, this is utter nonsense. According to the Department for Transport’s ‘Road Safety Good Practice Guide’, urban residential roads account for nearly 40% of all crashes (‘accidents’, according to DfT) and a high proportion of the casualties are children.The answer, according to recommendation 4.67, is that: ‘On residential access roads drivers need to be given visual cues that indicate strongly that this road space is part of the environment where people live, walk, talk and play.’

Not to put too fine a point on it, this is utter nonsense. According to the Department for Transport’s ‘Road Safety Good Practice Guide’, urban residential roads account for nearly 40% of all crashes (‘accidents’, according to DfT) and a high proportion of the casualties are children.The answer, according to recommendation 4.67, is that: ‘On residential access roads drivers need to be given visual cues that indicate strongly that this road space is part of the environment where people live, walk, talk and play.’

The road lobby isn’t all it might appear either! Road interests are advanced by something called the Association of British Drivers, a hang ’em, flog ’em and run ‘em down operation, composed largely of middle-aged men of the kind that wear trilby hats and grip the wheel with chamois leather driving gloves. Believing in broad terms that motoring should be fast, cheap and convenient, the ABD lobbies hard against speed cameras, taxation and road pricing, as one might expect. But Mark McArthur-Christie, the ABD’s Road Safety spokesman appears, to have gone native! After riding a Dawes Galaxy to work and rather enjoying the experience, Mark ‘didn’t bother’ replacing his car when it was written off, and is now car-free. ‘If I absolutely need a car, I hire it’, says the ABD man. For National Bike Week in June, he went a step further, organising a car, bike and bus Oxford commuter challenge.

The road lobby isn’t all it might appear either! Road interests are advanced by something called the Association of British Drivers, a hang ’em, flog ’em and run ‘em down operation, composed largely of middle-aged men of the kind that wear trilby hats and grip the wheel with chamois leather driving gloves. Believing in broad terms that motoring should be fast, cheap and convenient, the ABD lobbies hard against speed cameras, taxation and road pricing, as one might expect. But Mark McArthur-Christie, the ABD’s Road Safety spokesman appears, to have gone native! After riding a Dawes Galaxy to work and rather enjoying the experience, Mark ‘didn’t bother’ replacing his car when it was written off, and is now car-free. ‘If I absolutely need a car, I hire it’, says the ABD man. For National Bike Week in June, he went a step further, organising a car, bike and bus Oxford commuter challenge.

Most of our friends were agreed on one thing when Alexander arrived – we might previously have lived a car-free lifestyle as rootless ‘dinkies’, but all that was going to change. Sage nods all round.

Most of our friends were agreed on one thing when Alexander arrived – we might previously have lived a car-free lifestyle as rootless ‘dinkies’, but all that was going to change. Sage nods all round.