Forty years ago, Doctor Moulton demonstrated that 16-inch tyres offered lower rolling resistance than anyone thought. Controversially, he went on to prove that his own 17- inch tyre rolled as well (or even better) than its 27-inch equivalent. For many years, the ‘cooking’ Moultons were sold with smaller 16-inch tyres, or to be more precise, 16″ x 13/8″. Incidentally, there are three slightly different 16-inch formats, so its safer to use the international metric rim size: 349mm. Look on the tyre and you’ll usually see 37-349.The 37 refers to the width in millimetres (that’s the 13/8″ bit).

While sales of the Moulton were strong, these tyres became widely available, but with the decline in Moulton sales at the end of the 1960s, tyre companies lost interest, and the 349mm format began to fade away.

Fortunately, as we’ve recounted numerous times, this ‘ideal’ folding bike tyre size was saved – initially by the Bickerton (fitted only at the rear, of course), then the Micro, and from the late 1980s, the Brompton and later the Airframe. It might have been an ideal size, but by this time there was only one half-decent tyre left in mass production – the Raleigh Record.

In 1996, with the arrival of the race-bred Primo Comet, 349mm tyres were back at the cutting edge.The better tyres helped to sell bikes, and more bikes brought better tyres…There are now four main choices, and a number of interesting developments on the horizon.

Most of these tyres are available with or without a tough kevlar under-layer to resist punctures. Kevlar increases rolling resistance, but we’re not convinced it reduced punctures.The results of our small reader’s survey (sent out with December 2003 renewals) seems to confirm this.

Raleigh Record (37-349mm)

Are we serious? Well, they’re cheap, but thereafter it’s all negatives: the Record is heavier than the new breed, it punctures more frequently, rolls less well and is more difficult to remove from the rim. For very mean people who don’t mind mending a few punctures, a pair of Records will last 3,000-4,000 miles. But life’s too short, surely?

Points to watch: Prone to punctures, particularly when badly worn, but may outlive you.

Weight: 338g

Puncture resistance: Mediocre

Rolling resistance: Poor

Price: £5

Outlets: Less glamourous cycle shops

Primo Comet (37-349mm)

The story has it that American recumbent manufacturer Vision developed a small race- bred tyre, and licensed the technology to Cheng Shin in Taiwan, who succeeded in producing an everyday racing tyre for an everyday road price.The magic ingredients were a near-slick tread, and strong, but paper-thin reinforced sidewalls that rolled and flexed much better than the conventional kind, yet lasted almost as long.What also impressed about the Primo was its strikingly low weight of 201g a tyre – a saving of no less than 137g over a Raleigh Record. As if by magic, small wheeled bikes started to go much, much faster, and weigh less too. Strangely enough, considering the Primo’s light, supple construction, the tyres proved to be relatively puncture-proof, and (on tarmac, at least) the lack of tread has no negative effects. Needless to say, this is not a tyre for muddy or loose surfaces, and the sidewalls will be damaged if used with a dynamo, but the Primo remains a firm favourite with some.They’re surprisingly hard wearing too. With care (ie, no dynamo and no riding whilst flat), a Primo should last up to 3,000 miles and puncture around every 1,000. Eventually, the sidewalls become a bit frail, and cuts in the tread harbour glass and flint shards, causing more regular punctures.

The story has it that American recumbent manufacturer Vision developed a small race- bred tyre, and licensed the technology to Cheng Shin in Taiwan, who succeeded in producing an everyday racing tyre for an everyday road price.The magic ingredients were a near-slick tread, and strong, but paper-thin reinforced sidewalls that rolled and flexed much better than the conventional kind, yet lasted almost as long.What also impressed about the Primo was its strikingly low weight of 201g a tyre – a saving of no less than 137g over a Raleigh Record. As if by magic, small wheeled bikes started to go much, much faster, and weigh less too. Strangely enough, considering the Primo’s light, supple construction, the tyres proved to be relatively puncture-proof, and (on tarmac, at least) the lack of tread has no negative effects. Needless to say, this is not a tyre for muddy or loose surfaces, and the sidewalls will be damaged if used with a dynamo, but the Primo remains a firm favourite with some.They’re surprisingly hard wearing too. With care (ie, no dynamo and no riding whilst flat), a Primo should last up to 3,000 miles and puncture around every 1,000. Eventually, the sidewalls become a bit frail, and cuts in the tread harbour glass and flint shards, causing more regular punctures.

Early Primo tyres had natural brown sidewalls that soon looked shabby, but later examples were all-black, and some have reflective sidewalls too.There’s a kevlar option, but we’ve seen no evidence that it’s worth paying extra for.

Points to watch: Rolling resistance is so low that you may not notice a puncture before the rim hits the ground. And avoid the ultra-light 19mm (19-349) Primo unless you’re building a one-race special. Although light and free-running, it is unsuitable for road use and can fail rapidly.

Weight: 201g

Puncture resistance: Good

Rolling resistance: Excellent

Price: £15

Outlets: Rarer now, but try Avon Valley Cyclery or St John Street Cycles (see ads in back pages).

Brompton (yellow flash) (37-349mm)

By the late 1990s so many Brompton customers were fitting their own Primo tyres that Brompton decided to develop a road version for themselves. After a number of experiments, the now familiar ‘snakeskin’ tread pattern first appeared in early 2000 and was soon standard on all Brompton models, apart from the lowly C3.

By the late 1990s so many Brompton customers were fitting their own Primo tyres that Brompton decided to develop a road version for themselves. After a number of experiments, the now familiar ‘snakeskin’ tread pattern first appeared in early 2000 and was soon standard on all Brompton models, apart from the lowly C3.

With thin supple Primo-style sidewalls, and a tougher, but equally flexible (possibly more flexible) tread, the tyre was expected to have slightly inferior rolling performance to its racing forebear, but our tests found little difference, and engineers at Greenspeed (see graph) have actually recorded a modest improvement.This may be down to the rubber compound chosen – the Brompton tyre is quite hard, making it relatively puncture resistant and very long lasting. According to our reader’s survey, Brompton tyres have a life of 1,000 to 8,000 miles, with a mean figure of about 4,000 miles; something we’d agree with from experience. Puncture resistance seems to vary a great deal, but the mean figure is 1,060 miles – far in excess of any other tyre. Indeed, almost half our respondents had never experienced a puncture.The downside appears to be a lack of grip in the wet, particularly when running obliquely to white lines and low kerbs. The evidence for this is quite patchy, but sufficiently widespread to cause concern.

If the standard Brompton tyre is so good, surely the ‘green flash’ kevlar-lined version is even better? We don’t think it is. Our reader’s sample was small, but together with the evidence we’ve seen over the years, it suggests the kevlar tyre has a shorter life and is actually more vulnerable to punctures.

Points to watch: May lack grip in wet weather, particularly when new. Either ‘run in’ with care for a few weeks, or try buffing the tread with sandpaper before use!

Weight: 248g

Puncture resistance: Excellent

Rolling resistance: Excellent

Typical Price: £9.99 (kevlar ‘green flash’ tyre, about £16.25)

Stockists: All Brompton dealers

Schwalbe Marathon (37-349mm)

The Marathon is a newish tyre, allegedly developed from the long-established Swallow, which sold here back in the days when the Brits were a bit suspicious of the Germans and preferred to buy products with British-sounding names. Still, we’re all friends now, eh?

The Marathon is a newish tyre, allegedly developed from the long-established Swallow, which sold here back in the days when the Brits were a bit suspicious of the Germans and preferred to buy products with British-sounding names. Still, we’re all friends now, eh?

This is the only modern 16-inch tyre relying on ‘old-fashioned’ tyre construction, but the Marathon incorporates plenty of clever technology, including rubber with a high silica content to improve grip and a kevlar belt for puncture resistance.

The general consensus is that the Schwalbe is relatively puncture-proof compared to the lighter tyres, but our reader’s experiences seem to tell a different story.Your figures suggest average tyre life in the region of 2,300 miles, and punctures every 860 miles.There are many reasons why our results might not be scientific – for example, a tougher looking tyre is more likely to be fitted to a hard-ridden machine – but the evidence appears to suggest that they have a shorter service life and more punctures than their lighter (and cheaper) cousins.They can also be a tight fit on the rim, making punctures even more annoying. And according to the Greenspeed data (see graph), rolling resistance is rather higher – the Schwalbe absorbing as much as ten watts more per tyre than the Brompton. At18mph (the speed at which the tyres were tested) that relates to around 16% extra effort.Whatever the truth (and Greenspeed believes its test methods may exaggerate the differential) the Marathon is a safe, grippy tyre that looks effective, and it has rightly settled down as a popular option. For tough conditions and off-road use, it is probably the best choice.

The seriously puncture-proof Marathon Plus should also be available in this size soon, but Bohle UK was unable to confirm a date.

Points to watch: Vice-free, but stodgy performer

Weight: 340g

Puncture resistance: Good

Rolling resistance: Fair

Typical Price: £15

Stockists: Most small-wheeled bike dealers (see advertisements)

Schwalbe Stelvio (28-349mm)

The Stelvio is considerably narrower than the 37mm tyres, but as it retains the same ‘aspect ratio’ (ie, ratio of width to height), it also has a smaller overall diameter.The tyre will stretch to fit the 20mm rims fitted to the Brompton and most other 16-inch bikes these days, but the reduced tyre diameter means you’ll have to recalibrate your speedometer, and accept slightly lower gearing.

The Stelvio is considerably narrower than the 37mm tyres, but as it retains the same ‘aspect ratio’ (ie, ratio of width to height), it also has a smaller overall diameter.The tyre will stretch to fit the 20mm rims fitted to the Brompton and most other 16-inch bikes these days, but the reduced tyre diameter means you’ll have to recalibrate your speedometer, and accept slightly lower gearing.

The tyres feature just about every technology going – the sidewalls are paper thin, Primo- style, the centre of the tread is a slick, low-friction rubber, and the shoulders a grippy silica mix. Overall weight is marginally the lightest on the market at 196g.

Are they worth the money and the trouble? Being such a small tyre, the Stelvio is vulnerable to incorrect tyre pressures – Schwalbe recommends 85psi – 120psi, figures that most tyre pumps simply can’t reach. If run at too low a pressure, the tubes are liable to suffer from pinch punctures on bumps. Punctures do seem to be a problem generally, but there simply isn’t enough evidence to say for sure.

On a Brompton or Micro, the Stelvio serves only to give a spine-jarring ride and over-light steering for no detectable benefit, but this light, fast 120psi tyre might make sense on a fully-suspended bike such as the Moulton – preferably with the correct narrow rims. Provided you look after the tyres, and fit them to the right sort of machine, they may be the fastest 16-inch option.

Points to watch: Some potential for faster machines

Weight: 196g (you can save a further 9g per tyre by fitting Schwalbe 32mm inner tubes)

Puncture resistance: Poor

Rolling resistance: Excellent

Price: £13.50 (including UK postage)

Stockist: Westcountry Recumbents [rob@wrhpv.com]

Conclusion

If weight really matters, the Primo still has much to offer, although you’d be well advised to stock up while they’re still widely available. For racing, it’s probably fair to say that the Schwalbe Stelvio is the best, although we’d hesitate to recommend it for road use.The overall winner, in terms of value for money, life, puncture resistance and rolling resistance, just has to be the standard Brompton tyre.The only question mark seems to be wet weather grip – in all other respects, this is a remarkable tyre.

Incidentally, the tyres tested above are rated at all sorts of pressures, but please ignore such phrases as ‘inflate to 100psi’ (Brompton, in this example).Whatever the graph might seem to indicate, these figures are maximum pressures, and will only give the results indicated on a perfectly smooth surface. For most riders, on typical road surfaces, a lower pressure will give both lower rolling resistance and greater comfort.

A good general guide is to sit on the bike and adjust the tyre pressures front and rear until the tyre just begins to bulge out above the road contact patch.That pressure (always higher for the rear tyre, of course) might be 100psi, 80, 60 or even less, but it will be close to ideal for you, your bicycle and your tyres. On the road, high frequency vibration means too much pressure, and a ‘wallowing’ ride, too little. If this all sounds like hard work, aim for about 65psi front and 75psi at the rear.

![]()

Briefly, nothing folds smaller (without exception), no other 16-inch folder rides so well (without exception, unless the Russians have produced something we haven’t seen yet), and nothing folds so neatly and so fast.These are the killer attributes that have made the Brompton the commuter bike par excellence and kept the order books full for this small British company, now possibly the largest bicycle manufacturer (as opposed to assembler – ie, bolting on bits) in the UK. One could argue that Pashley still has the Post Office bike contract and the Taiwanese claim to be making things, rather than assembling them, in the Welsh valleys these days, but enough hair-splitting.

Briefly, nothing folds smaller (without exception), no other 16-inch folder rides so well (without exception, unless the Russians have produced something we haven’t seen yet), and nothing folds so neatly and so fast.These are the killer attributes that have made the Brompton the commuter bike par excellence and kept the order books full for this small British company, now possibly the largest bicycle manufacturer (as opposed to assembler – ie, bolting on bits) in the UK. One could argue that Pashley still has the Post Office bike contract and the Taiwanese claim to be making things, rather than assembling them, in the Welsh valleys these days, but enough hair-splitting. We thought we’d need a micrometer to spot the change, but with the bike unfolded, it leaps out at you.Where the curved section of the frame tube used to reach almost to the handlebar stem, the straight bits either side of the hinge give the bike a noticeably different form.

We thought we’d need a micrometer to spot the change, but with the bike unfolded, it leaps out at you.Where the curved section of the frame tube used to reach almost to the handlebar stem, the straight bits either side of the hinge give the bike a noticeably different form. We mentioned this back in October, and although it may not sound the most exciting advance, CAD techniques have enabled the Brompton boffins to reduce the weight of the front pannier bag frame from 690g to 400g.This substantial cut has been achieved through a mixture of light alloy tubes and nylon castings. It’s all very high-tech and Bromptonesque, and makes a noticeable difference to the weight of the pannier bag.With the panniers down in price to £40 – £70 (according to spec, and including the new frame) there’s never been a better time to upgrade that front luggage. If you have a serviceable bag already, the new frame costs about £25.50 on its own.

We mentioned this back in October, and although it may not sound the most exciting advance, CAD techniques have enabled the Brompton boffins to reduce the weight of the front pannier bag frame from 690g to 400g.This substantial cut has been achieved through a mixture of light alloy tubes and nylon castings. It’s all very high-tech and Bromptonesque, and makes a noticeable difference to the weight of the pannier bag.With the panniers down in price to £40 – £70 (according to spec, and including the new frame) there’s never been a better time to upgrade that front luggage. If you have a serviceable bag already, the new frame costs about £25.50 on its own. The dynamo lights on the Brompton have changed out of all recognition in the last few years. Early dynamos whined and seized, while dim bulbs fought to provide illumination.The arrival of a Basta LED rear light and halogen front lamp brought a dramatic improvement a few years ago, and there’s now an Axa HR dynamo too. It’s hard to say how useful this is, but it’s quiet, it rolls easily, and light output, even at low speed, is excellent.

The dynamo lights on the Brompton have changed out of all recognition in the last few years. Early dynamos whined and seized, while dim bulbs fought to provide illumination.The arrival of a Basta LED rear light and halogen front lamp brought a dramatic improvement a few years ago, and there’s now an Axa HR dynamo too. It’s hard to say how useful this is, but it’s quiet, it rolls easily, and light output, even at low speed, is excellent. Another small, but worthwhile development. A tiny plastic rod is fixed into the brake calliper and the previously exposed inner cable is protected from the elements by a flexible rubber gaiter. Brompton brake cables are prone to water ingress because the cables point upwards, so this tiny change should help improve cable life and braking performance on all-weather bikes. Unfortunately, older bikes can only be upgraded by drilling the calliper, but the gaiters cost only £1.50 each.

Another small, but worthwhile development. A tiny plastic rod is fixed into the brake calliper and the previously exposed inner cable is protected from the elements by a flexible rubber gaiter. Brompton brake cables are prone to water ingress because the cables point upwards, so this tiny change should help improve cable life and braking performance on all-weather bikes. Unfortunately, older bikes can only be upgraded by drilling the calliper, but the gaiters cost only £1.50 each. A long long overdue change – the handlebar locking catch has been replaced with a new design that should help to keep the folded handlebars under control, and prevent them flying open at inconvenient moments. A great safety upgrade for older bikes at £3.71, and highly recommended.

A long long overdue change – the handlebar locking catch has been replaced with a new design that should help to keep the folded handlebars under control, and prevent them flying open at inconvenient moments. A great safety upgrade for older bikes at £3.71, and highly recommended.

This review was published in February 2004. The Bliss has long since disappeared, and electric bikes have changed a great deal. Interesting historical item though!

This review was published in February 2004. The Bliss has long since disappeared, and electric bikes have changed a great deal. Interesting historical item though!

This is the neat bit.The brushless DC motor measures only 130mm in diameter, and 100mm in width. So if the engineers at Pashley, Brompton or Dahon are reading, yes, this sort of thing could be squeezed into the front wheel of your folding bikes. At a rated output of 180 watts, it’s not particularly powerful, but the peak power of 288 watts at 8mph is useful enough, and combined with the low gearing, gives the Bliss a capacity to climb just about anything, albeit at a fairly sedate speed. The motor doesn’t so much buzz or whine, as emit a pleasantly high-tech harmonic, just like state-of-the-art Millennial machines are supposed to do.

This is the neat bit.The brushless DC motor measures only 130mm in diameter, and 100mm in width. So if the engineers at Pashley, Brompton or Dahon are reading, yes, this sort of thing could be squeezed into the front wheel of your folding bikes. At a rated output of 180 watts, it’s not particularly powerful, but the peak power of 288 watts at 8mph is useful enough, and combined with the low gearing, gives the Bliss a capacity to climb just about anything, albeit at a fairly sedate speed. The motor doesn’t so much buzz or whine, as emit a pleasantly high-tech harmonic, just like state-of-the-art Millennial machines are supposed to do.

The Lowlander leaves London at close to midnight, splitting and arriving in both Glasgow and Edinburgh just after 7am, while the Highland portions leave London at 9.05pm as one massive 16-coach train (currently the longest scheduled passenger service on Britain’s railways) before splitting at Edinburgh into more manageable chunks. Despite a leisurely schedule, arrival times are 7.35 in Aberdeen, 8.30 in Inverness, and 9.43am in Fort William. Coming the other way, all trains are scheduled to arrive in London between 7.30 and 8am, making the sleeper something of a favourite with businessmen facing an early meeting in the capital.

The Lowlander leaves London at close to midnight, splitting and arriving in both Glasgow and Edinburgh just after 7am, while the Highland portions leave London at 9.05pm as one massive 16-coach train (currently the longest scheduled passenger service on Britain’s railways) before splitting at Edinburgh into more manageable chunks. Despite a leisurely schedule, arrival times are 7.35 in Aberdeen, 8.30 in Inverness, and 9.43am in Fort William. Coming the other way, all trains are scheduled to arrive in London between 7.30 and 8am, making the sleeper something of a favourite with businessmen facing an early meeting in the capital.

In the south of England, Rogart would be considered a hamlet, but in Highland terms, it’s quite a regional centre, with a good pub/restaurant and the sort of general store that stocks everything from bootlaces to smoked salmon. For walkers, the moors and peaks are just off the station platform, and we spent many happy hours dodging sleet showers to peer down at our tiny carriage from wind-blasted peaks with unpronounceable names. For cyclists, all roads except the A9 are quiet, back roads virtually car-free, and the local drivers courteous without exception.The easiest ride of all is to take the train ten miles up the valley to Lairg and cruise back: down hill all the way, with a prevailing tailwind.

In the south of England, Rogart would be considered a hamlet, but in Highland terms, it’s quite a regional centre, with a good pub/restaurant and the sort of general store that stocks everything from bootlaces to smoked salmon. For walkers, the moors and peaks are just off the station platform, and we spent many happy hours dodging sleet showers to peer down at our tiny carriage from wind-blasted peaks with unpronounceable names. For cyclists, all roads except the A9 are quiet, back roads virtually car-free, and the local drivers courteous without exception.The easiest ride of all is to take the train ten miles up the valley to Lairg and cruise back: down hill all the way, with a prevailing tailwind.

How do you explain Jan Lundberg? He isn’t at all what one would expect from his family background. What do you say about a man who has torn up his driveway and planted a vegetable garden in its place? Perhaps he is just odd, or maybe it is because he lives in Arcata, California, a small town in the far northern part of the state. Arcata is in redwood country – cool, damp and foggy. Life among the redwood trees takes some strange turns for some people. It has happened before.

How do you explain Jan Lundberg? He isn’t at all what one would expect from his family background. What do you say about a man who has torn up his driveway and planted a vegetable garden in its place? Perhaps he is just odd, or maybe it is because he lives in Arcata, California, a small town in the far northern part of the state. Arcata is in redwood country – cool, damp and foggy. Life among the redwood trees takes some strange turns for some people. It has happened before.

Our advocacy of electric bikes continues to cause controversy. Some readers have made the point that they never see electric bikes on the road, so why bother testing them? Had ‘A to B’ been around in 1903, we would certainly be trying the new steam and petroleum-powered automobiles. They’d be slow, unreliable and offer a limited range. No doubt we’d get letters telling us that they were elitist, expensive, never likely to replace the horse, etc, etc.

Our advocacy of electric bikes continues to cause controversy. Some readers have made the point that they never see electric bikes on the road, so why bother testing them? Had ‘A to B’ been around in 1903, we would certainly be trying the new steam and petroleum-powered automobiles. They’d be slow, unreliable and offer a limited range. No doubt we’d get letters telling us that they were elitist, expensive, never likely to replace the horse, etc, etc.

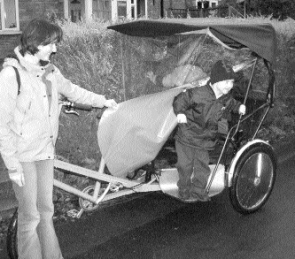

Recumbent bikes and trikes are cumbersome things, which helps to explain why they remain relatively unpopular for day-to-day use, although for recreation and sheer entertainment, laid-back cycling is unbeatable.

Recumbent bikes and trikes are cumbersome things, which helps to explain why they remain relatively unpopular for day-to-day use, although for recreation and sheer entertainment, laid-back cycling is unbeatable.

If you haven’t ridden a well-sorted recumbent trike, you’ve missed out on one of life’s Great Experiences. And by any standards, this well-balanced and agile, yet forgiving, machine is an experience you’re unlikely to forget in a hurry. Like all the best mid-engined sports cars, geometry and weight distribution have been chosen to give handling that’s broadly neutral – in other words, should you over-cook things on a sharp bend, the GT3 will neither plough straight on, or head for the apex.We rode the trike in all sorts of conditions, with a variety of tyre pressures and several drivers, and the thing cornered throughout as though on rails.This seems to hold true on dry surfaces, wet surfaces and – a Somerset speciality – manure-covered surfaces.You need to concentrate, because things happen very quickly when you’re sitting on the ground, but we’d guess that’s part of the fun with a mid-engined sports car too.With a bit of familiarity, you soon find yourself cruising through corners that would send a cyclist sliding into the hedge. Once in a while, the front Primo tyres scrabble for grip, and occasionally the rear end ducks and dives on a bump, but at bicycle speeds, there’s plenty in reserve.

If you haven’t ridden a well-sorted recumbent trike, you’ve missed out on one of life’s Great Experiences. And by any standards, this well-balanced and agile, yet forgiving, machine is an experience you’re unlikely to forget in a hurry. Like all the best mid-engined sports cars, geometry and weight distribution have been chosen to give handling that’s broadly neutral – in other words, should you over-cook things on a sharp bend, the GT3 will neither plough straight on, or head for the apex.We rode the trike in all sorts of conditions, with a variety of tyre pressures and several drivers, and the thing cornered throughout as though on rails.This seems to hold true on dry surfaces, wet surfaces and – a Somerset speciality – manure-covered surfaces.You need to concentrate, because things happen very quickly when you’re sitting on the ground, but we’d guess that’s part of the fun with a mid-engined sports car too.With a bit of familiarity, you soon find yourself cruising through corners that would send a cyclist sliding into the hedge. Once in a while, the front Primo tyres scrabble for grip, and occasionally the rear end ducks and dives on a bump, but at bicycle speeds, there’s plenty in reserve. Hill climbing is a bit disappointing, not because the GT3 climbs particularly slowly, but because the climbs are markedly slower than the descents. Actually, the trike maintains a good pace on the sort of mild nagging gradients that might depress a bicyclist, but on steeper climbs, the bicycle is quicker, leaving the trike rider to sit it out and think about the fun they’ll have going down the other side.

Hill climbing is a bit disappointing, not because the GT3 climbs particularly slowly, but because the climbs are markedly slower than the descents. Actually, the trike maintains a good pace on the sort of mild nagging gradients that might depress a bicyclist, but on steeper climbs, the bicycle is quicker, leaving the trike rider to sit it out and think about the fun they’ll have going down the other side.

The carrying capacity of a conventional bike shouldn’t be underestimated – it’s amazing what you can fit into a decent set of panniers. However, with cycling as my main form of transport, I often wished I could carry heavier or awkwardly-shaped items.The obvious solution was a trailer, and I picked up a great hand-built one, but found that for a number of reasons it didn’t quite suit my needs. Most crucially, with a trailer you only have the extra cargo capacity when you’ve bothered to lug it round with you.

The carrying capacity of a conventional bike shouldn’t be underestimated – it’s amazing what you can fit into a decent set of panniers. However, with cycling as my main form of transport, I often wished I could carry heavier or awkwardly-shaped items.The obvious solution was a trailer, and I picked up a great hand-built one, but found that for a number of reasons it didn’t quite suit my needs. Most crucially, with a trailer you only have the extra cargo capacity when you’ve bothered to lug it round with you. Load carrying is done primarily in so-called ‘FreeLoaders’: Nylon flaps which attach to the racks. These are open at the top, so shouldn’t be used simply as bags (I initially made that mistake and lost a few things as a result!).The idea is that you put your shopping in bags and put the bags in the FreeLoaders.The open- topped design allows you to carry large or awkwardly- shaped loads, such as wooden planks.

Load carrying is done primarily in so-called ‘FreeLoaders’: Nylon flaps which attach to the racks. These are open at the top, so shouldn’t be used simply as bags (I initially made that mistake and lost a few things as a result!).The idea is that you put your shopping in bags and put the bags in the FreeLoaders.The open- topped design allows you to carry large or awkwardly- shaped loads, such as wooden planks. Most significantly, the design is not as well suited to British weather as it might be, which is hardly surprising, as the designers are based in Nevada.The FreeRadical frame is made of steel, while the racks that slot into it are aluminium. Given a heavy shower the vertical tubes of the FreeRadical collect water, and corrosion occurs rapidly, all the more so because of the interface between the two metals.Thankfully, this problem can be avoided by wrapping some waterproof tape around the junction between the racks and their sockets. Another damp-related problem I encountered was that after being left outside overnight, the SnapDeck absorbed water and warped. I’ve since painted it with exterior varnish, which seems to have worked.

Most significantly, the design is not as well suited to British weather as it might be, which is hardly surprising, as the designers are based in Nevada.The FreeRadical frame is made of steel, while the racks that slot into it are aluminium. Given a heavy shower the vertical tubes of the FreeRadical collect water, and corrosion occurs rapidly, all the more so because of the interface between the two metals.Thankfully, this problem can be avoided by wrapping some waterproof tape around the junction between the racks and their sockets. Another damp-related problem I encountered was that after being left outside overnight, the SnapDeck absorbed water and warped. I’ve since painted it with exterior varnish, which seems to have worked. It’s a measure of just how in tune we are, that we immediately thought a Glowbag was something you planted tomatoes in (don’t bother – home-made compost is just as effective), but it turns out to be a bag that, er, glows.

It’s a measure of just how in tune we are, that we immediately thought a Glowbag was something you planted tomatoes in (don’t bother – home-made compost is just as effective), but it turns out to be a bag that, er, glows.

There’s a certain romance associated with human power.You know the sort of thing – the bronzed noble savage, pulsating limbs, rippling muscles, incredible loads, and not even a whiff of nitrous oxide. Ooh, enough, enough! The reality – as any gap-year rickshaw pilot will tell you – can be very different. Pedal power can move surprising loads at modest speeds on the flat, but come to a hill and rolling resistance becomes the least of your worries…We regularly drag trailing loads of 70kg uphill to the Post Office, so we know a little about these things (and generally choose an electric bike for the job too).

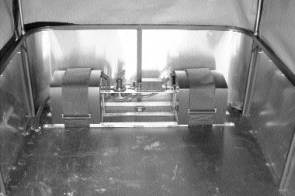

There’s a certain romance associated with human power.You know the sort of thing – the bronzed noble savage, pulsating limbs, rippling muscles, incredible loads, and not even a whiff of nitrous oxide. Ooh, enough, enough! The reality – as any gap-year rickshaw pilot will tell you – can be very different. Pedal power can move surprising loads at modest speeds on the flat, but come to a hill and rolling resistance becomes the least of your worries…We regularly drag trailing loads of 70kg uphill to the Post Office, so we know a little about these things (and generally choose an electric bike for the job too). Cycles Maximus is the creation of Ian Wood, a Bath publican (owner of drinking establishments, for overseas readers).The HPV business started in a couple of lock- ups back in 1997, when Ian and business partner Tom Nesbitt set to work designing, and ultimately producing, a lighter, faster version of the classic rickshaw, or pedicab as they’re becoming known. In April 2001, the company moved to a 5,000 square foot factory unit, and notched production up a gear.Today, Pedicabs, and increasingly, Cargo trikes, roll off the assembly line at the rate of about one a week, making Cycles Maximus the biggest producer in Europe and very possibly anywhere outside the Third World.Total sales to date exceed 160, of which around 100 work in London, with smaller pockets in York, Edinburgh and elsewhere. Most of the Pedicabs are pedal-powered, carrying passengers over short distances, but Cargo trikes are more likely to include electric-assist and undertake longer journeys with bigger loads.

Cycles Maximus is the creation of Ian Wood, a Bath publican (owner of drinking establishments, for overseas readers).The HPV business started in a couple of lock- ups back in 1997, when Ian and business partner Tom Nesbitt set to work designing, and ultimately producing, a lighter, faster version of the classic rickshaw, or pedicab as they’re becoming known. In April 2001, the company moved to a 5,000 square foot factory unit, and notched production up a gear.Today, Pedicabs, and increasingly, Cargo trikes, roll off the assembly line at the rate of about one a week, making Cycles Maximus the biggest producer in Europe and very possibly anywhere outside the Third World.Total sales to date exceed 160, of which around 100 work in London, with smaller pockets in York, Edinburgh and elsewhere. Most of the Pedicabs are pedal-powered, carrying passengers over short distances, but Cargo trikes are more likely to include electric-assist and undertake longer journeys with bigger loads.

The motor is continuously rated at 250 watts, which brings it within current electric tricycle legislation, so the Lynch- motored trike doesn’t need an MOT, tax disc and all the rest.With a modest load and on modest gradients, 250 watts will keep you chugging gently along all day. Our motor was geared for a comfortable 9mph, but the gearing is up to you, provided assistance is not available above 15mph.

The motor is continuously rated at 250 watts, which brings it within current electric tricycle legislation, so the Lynch- motored trike doesn’t need an MOT, tax disc and all the rest.With a modest load and on modest gradients, 250 watts will keep you chugging gently along all day. Our motor was geared for a comfortable 9mph, but the gearing is up to you, provided assistance is not available above 15mph.

Thanks to a state-of- the-art German charger, recharging is reasonably quick: A 90% charge takes 41/2 hours, followed by a lengthy ‘trickle’ charge, completed in another four hours or so. Unfortunately, we set off after four hours, which took the machine only 121/2 miles.That’s much less than we expected, which might have something to do with the drag characteristics of the weather shield, which was fitted on the way home to keep the 100kg load cheerful.

Thanks to a state-of- the-art German charger, recharging is reasonably quick: A 90% charge takes 41/2 hours, followed by a lengthy ‘trickle’ charge, completed in another four hours or so. Unfortunately, we set off after four hours, which took the machine only 121/2 miles.That’s much less than we expected, which might have something to do with the drag characteristics of the weather shield, which was fitted on the way home to keep the 100kg load cheerful.

Dynamo lights have many advantages.They’re always on call, lightweight, and extra- bright, but traditional dynamos are noisy, inefficient and unreliable.These days, there’s a renewed interest in hub dynamos, which are virtually silent and more reliable, but expensive to buy and fit.We’ve looked at the best bottle dynamos we could find, to see if they’re: (a) worth the extra over a conventional bottle and/or (b) comparable to a hub.

Dynamo lights have many advantages.They’re always on call, lightweight, and extra- bright, but traditional dynamos are noisy, inefficient and unreliable.These days, there’s a renewed interest in hub dynamos, which are virtually silent and more reliable, but expensive to buy and fit.We’ve looked at the best bottle dynamos we could find, to see if they’re: (a) worth the extra over a conventional bottle and/or (b) comparable to a hub. The Dymotec 6 costs £38, the S6 £110, and the S12 (complete with 12v versions of the Lumotec Oval Plus front light and Toplight Plus rear lights), no less than £300. Sounds like a reasonable budget for a bicycle. But for engineers everywhere, this is more or less the dream spec for a dynamo: 12 volts, 6.2 watts and 60% efficiency. For the rest of us, let us just say it’s solidly made, reliable and efficient.

The Dymotec 6 costs £38, the S6 £110, and the S12 (complete with 12v versions of the Lumotec Oval Plus front light and Toplight Plus rear lights), no less than £300. Sounds like a reasonable budget for a bicycle. But for engineers everywhere, this is more or less the dream spec for a dynamo: 12 volts, 6.2 watts and 60% efficiency. For the rest of us, let us just say it’s solidly made, reliable and efficient. We tested the S12 with Busch & Müller’s wonderful Lumotec Oval Plus front lamp and Toplight Plus rear lamp, produced in 12 volt versions specifically for this dynamo. Both have a standlight function too – the rear LEDs continue to burn at full brightness for about five minutes, while the front switches to a single white LED that lasts for ‘at least’ ten minutes. Ever tried waiting for a standlight to go out when there’s something good on the telly? Should your unsoldered connectors drop off, the front standlight is as powerful as some elderly filament bulbs, and easily bright enough to get you home.

We tested the S12 with Busch & Müller’s wonderful Lumotec Oval Plus front lamp and Toplight Plus rear lamp, produced in 12 volt versions specifically for this dynamo. Both have a standlight function too – the rear LEDs continue to burn at full brightness for about five minutes, while the front switches to a single white LED that lasts for ‘at least’ ten minutes. Ever tried waiting for a standlight to go out when there’s something good on the telly? Should your unsoldered connectors drop off, the front standlight is as powerful as some elderly filament bulbs, and easily bright enough to get you home. Unlike the B&M S12, this is a six volt device, so you can use it with conventional six volt lamps, provided you seek and destroy those pesky zener diodes. It’s also relatively cheap at £70 – a full £40 less than the B&M S6, which has a lower output. Efficiency is claimed to be 65-75%, so with our measured power output of only 2.6 watts, we estimate a power requirement of less than four watts.With such a low demand, the wheel can be spun quite easily – you can’t feel it on the road.The coasting speed was reduced from 15.3 to 15.2 mph – a barely discernible effect.

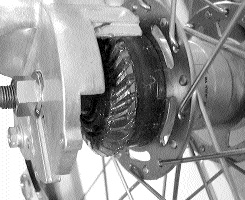

Unlike the B&M S12, this is a six volt device, so you can use it with conventional six volt lamps, provided you seek and destroy those pesky zener diodes. It’s also relatively cheap at £70 – a full £40 less than the B&M S6, which has a lower output. Efficiency is claimed to be 65-75%, so with our measured power output of only 2.6 watts, we estimate a power requirement of less than four watts.With such a low demand, the wheel can be spun quite easily – you can’t feel it on the road.The coasting speed was reduced from 15.3 to 15.2 mph – a barely discernible effect. Shaft drives look great on paper, trading that grubby old chain for a completely sealed unit – no gear teeth, no oil, no grime, and no hassle. In reality, they’re relatively inefficient, noisy, heavy and expensive. Altering the gear ratio is a major engineering job, and even measuring the ratio can be complex. Forget what the salesmen say.The chain remains with us today – essentially unchanged for over 100 years – because it’s a damn good solution, unmatched by older and more recent inventions, such as the toothed rubber belt, shaft, oscillating rods, hydraulic, electric and all the rest.

Shaft drives look great on paper, trading that grubby old chain for a completely sealed unit – no gear teeth, no oil, no grime, and no hassle. In reality, they’re relatively inefficient, noisy, heavy and expensive. Altering the gear ratio is a major engineering job, and even measuring the ratio can be complex. Forget what the salesmen say.The chain remains with us today – essentially unchanged for over 100 years – because it’s a damn good solution, unmatched by older and more recent inventions, such as the toothed rubber belt, shaft, oscillating rods, hydraulic, electric and all the rest.

Sussex markets the steel-framed shaft-drive folder quite widely (you can buy it in the US for $385), but the alloy-framed bike is a more substantial, attractive, and unusually cleanly styled machine.The frame is finished (rather unnecessarily one might think) in lustrous silver metallic paint.The main hinge is a monstrous alloy block in classic Far Eastern style, but it works well enough and incorporates a clever safety device.The pin carrying the quick-release runs in the rear part of the hinge, and when engaged, it drops into a hole in the front part, locking the hinge shut. Even when the quick-release is unfastened, the hinge will not open until the pin is lifted. Simple and effective.The lighter handlebar stem hinge has a similar fitting.

Sussex markets the steel-framed shaft-drive folder quite widely (you can buy it in the US for $385), but the alloy-framed bike is a more substantial, attractive, and unusually cleanly styled machine.The frame is finished (rather unnecessarily one might think) in lustrous silver metallic paint.The main hinge is a monstrous alloy block in classic Far Eastern style, but it works well enough and incorporates a clever safety device.The pin carrying the quick-release runs in the rear part of the hinge, and when engaged, it drops into a hole in the front part, locking the hinge shut. Even when the quick-release is unfastened, the hinge will not open until the pin is lifted. Simple and effective.The lighter handlebar stem hinge has a similar fitting.

Yes, ten years and 61 editions ago, we started publishing the diminutive ‘Folder’ magazine that evolved into A to B. Thanks to all those individuals who’ve helped in various ways over the years (if only by subscribing), and to the companies that have backed us from Day One – shops such as Avon Valley, Cyclecare, Cycle Heaven and Norman Fay, and manufacturers: Andrew Ritchie of Brompton (subscriber 30), Hanz Scholtz of Bike Friday (55) and Mark Sanders of Strida (91).We now have more than 2,400 subscribers, incidentally…

Yes, ten years and 61 editions ago, we started publishing the diminutive ‘Folder’ magazine that evolved into A to B. Thanks to all those individuals who’ve helped in various ways over the years (if only by subscribing), and to the companies that have backed us from Day One – shops such as Avon Valley, Cyclecare, Cycle Heaven and Norman Fay, and manufacturers: Andrew Ritchie of Brompton (subscriber 30), Hanz Scholtz of Bike Friday (55) and Mark Sanders of Strida (91).We now have more than 2,400 subscribers, incidentally…

The real problem is that no-one has yet dreamed up a practical way of refuelling a vehicle of this kind, so filling stations are a bit thin on the ground. The general consensus is that robot actuation will be required, as the risks of (a) some clown blowing up the immediate neighbourhood or (b) inflating his jacket and floating off into the stratosphere, are not insignificant.

The real problem is that no-one has yet dreamed up a practical way of refuelling a vehicle of this kind, so filling stations are a bit thin on the ground. The general consensus is that robot actuation will be required, as the risks of (a) some clown blowing up the immediate neighbourhood or (b) inflating his jacket and floating off into the stratosphere, are not insignificant.

For 2003, Stuff invited alternative transport manufacturers to display their wares in a ‘Stuff the Congestion Charge’ zone. Thus, the bicycle world was represented by Brompton and Airnimal, two suitably techie folding machines, plus the single speed Bike-in-a- Bag; arguably less techie, but useful enough for the young man with neither money nor sense.

For 2003, Stuff invited alternative transport manufacturers to display their wares in a ‘Stuff the Congestion Charge’ zone. Thus, the bicycle world was represented by Brompton and Airnimal, two suitably techie folding machines, plus the single speed Bike-in-a- Bag; arguably less techie, but useful enough for the young man with neither money nor sense.

If you ride a bicycle you will probably already know of Josie Dew, patron saint of cycle touring and diminutive travel writer, whose previous volumes The Wind in my Wheels, Travels in a Strange State, A Ride in the Neon Sun and The Sun in my Eyes, have rightly become classics of their kind.Well, they have at A to B Towers, anyway.

If you ride a bicycle you will probably already know of Josie Dew, patron saint of cycle touring and diminutive travel writer, whose previous volumes The Wind in my Wheels, Travels in a Strange State, A Ride in the Neon Sun and The Sun in my Eyes, have rightly become classics of their kind.Well, they have at A to B Towers, anyway.

The road from A to B can be strewn with legal hurdles. Send your queries to Russell Jones & Walker, Solicitors, c/o A to B magazine

The road from A to B can be strewn with legal hurdles. Send your queries to Russell Jones & Walker, Solicitors, c/o A to B magazine