This lecture was originally presented by author Tony Hadland at the CYCLE 2002 show in London, September 2002.The emphasis is on British- designed machines and on foreign portables that had a significant impact in the UK. ‘Portable’ is used inclusively to represent folding, separable and demountable cycles.

This lecture was originally presented by author Tony Hadland at the CYCLE 2002 show in London, September 2002.The emphasis is on British- designed machines and on foreign portables that had a significant impact in the UK. ‘Portable’ is used inclusively to represent folding, separable and demountable cycles.

In The Beginning…

As early as 1881, the journalist Henry Sturmey wrote: ‘The idea of putting a bicycle into a bag is, indeed, a queer one, but of considerable value for all that, in these days of high railway charges’. William Grout had recently invented his ‘Portable’, an Ordinary or High Wheeler bicycle that could be packed into a relatively small bag.The big front wheel unbolted into four segments (solid tyres have their advantages!) and the spine of the bike folded in two. But the Grout Portable cost two or three times as much as a standard ‘Penny Farthing’, itself not cheap.The class of people who could afford it were not the sort willing to spend ten minutes grovelling about with spanners and wrestling bits of bicycle on a railway platform, while their social inferiors tittered in the background.The Grout Portable therefore did not catch on.

About this time, tricycles were set to eclipse the High Bicycle in popularity, being easier and safer to ride. But the problem with tricycles was getting them through doorways.Therefore many were made to reduce in width.The axle on which the two wheels were mounted might be constructed on a folding system, so that all three wheels could be swung into line. Alternatively, the axle might be made to telescope to a reduced width.The modern ‘safety’ bicycle soon saw off the penny-farthings and greatly reduced the popularity of trikes. Nonetheless, compressible tricycles were available for well over twenty years.

About this time, tricycles were set to eclipse the High Bicycle in popularity, being easier and safer to ride. But the problem with tricycles was getting them through doorways.Therefore many were made to reduce in width.The axle on which the two wheels were mounted might be constructed on a folding system, so that all three wheels could be swung into line. Alternatively, the axle might be made to telescope to a reduced width.The modern ‘safety’ bicycle soon saw off the penny-farthings and greatly reduced the popularity of trikes. Nonetheless, compressible tricycles were available for well over twenty years.

A Military Interlude

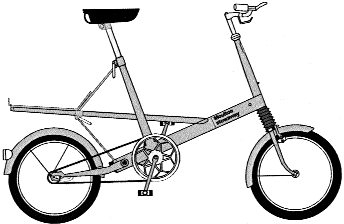

The Pederson. This example is one of many later imitations

At the end of the 19th century and in the early years of the 20th, there was considerable interest in military folding bicycles.Various nations, including the French, Dutch, Italians and British, experimented with them. In Britain, the Danish engineer Mikael Pedersen introduced a ‘Folding & Military’ version of his famous thin-tube bicycle, that was claimed to weigh a mere 15lb. In reality, it separated rather than folded (the two parts could be held together with a strap) and the late John Pinkerton’s example weighed 29lb.There is a lesson here about accepting bicycle manufacturers’ claims! Perhaps the prototype did weigh 15lbs. But in series production, weight often creeps up as consumer use reveals the inadequacies of design and detailing, and as cost pressures encourage the use of cheaper, heavier materials and components. Anyway, the British army did not adopt the Pedersen and the ‘Folding & Military’ version was phased out after four years.

An early British military folder, but not necessarily a BSA...

There were certainly folding (but otherwise conventional) diamond-frame safety bicycles commissioned by the British War Office in the First World War. These typically had a simple hinge in both the top tube and down tube, sometimes with additional reinforcing tubes linking the top and down tubes, adjacent to the hinges.These machines are often said to be BSAs, though in reality that company made few.The confusion arises from the widespread use by frame-makers of BSA fittings, such as lugs and bottom bracket shells.

In the Second World War, BSA and Raleigh certainly did make folding military cycles. BSA’s so-called ‘Parabike’ was by far the best known. (Interestingly, BSA did not formally adopt the name ‘Parabike’ until after the war, when they used it for a non-folding toy version.) The Parabike’s twin top and down tubes were formed by continuing the chain and seat stays forward to the head tube, a form of construction possibly suggested by the Moorson company’s twin-tube lightweights.There are numerous myths about Parabikes being used in large numbers by paratroopers in combat situations. I know of not one case that has been authenticated. Certainly, Parabikes were tested, and training routines evolved, documented and carried out. But when you think about it, the last thing a paratrooper (already burdened with a huge backpack and a rifle) needed when dropped into the flat and boggy fields around Arnhem was a folding bicycle to make him an even easier target for the waiting German machine gunners. Hence, large numbers of these The Parabike – it may never have seen action machines ended up being ridden in non-combat situations, behind the lines and on military bases. Many were sold off for civilian use after the war. The Parabike was significant, however, because it made the general public aware of the concept of folding bicycles. It was also quite elegant and at least five different companies have produced derivatives, not all of which folded.

The Parabike - it may never have seen action

A Glimpse of the Future

…the last thing a paratrooper needed… was a folding bicycle to make him an even easier target…

During the Second World War, Cycling magazine gave a glimpse of the future when in 1942 it reviewed Le Petit Bi. Designed by A.J. Marcelin of Paris in the late 1930s, this was probably the first small-wheeled, open-framed, unisex, folding bike-in-a-bag brought into the UK. It was allegedly made in steel and aluminium versions, solo and tandem.The original solo version had a squat triangulated non-folding frame, the size reduction being achieved by elegant folding handlebars and a long telescopic seat tube.The machine could be parked vertically, for instance in a wardrobe, standing on its rear pannier rack.

Le Petit Bi seems to have achieved a certain cachet with intellectuals: the philosopher Sartre and the artist Picabia were both photographed riding it. A post-war version incorporated a frame hinge, making it even more compact when folded.There is no evidence that Le Petit Bi was sold in the UK but it seems to have had some early post- war influence on the Continent and in Japan. In the late 1940s, the Japanese cycle trade sent a research mission to Europe seeking ideas to copy. By 1953, the Silk Road cycle company was selling its Road Puppy small-wheeled folder in Singapore. It is probably no coincidence that the Road Puppy was similar to the post-war version of Le Petit Bi.

The Moulton Revolution

The Stowaway looked much like any other Moulton, but it incorporated a clever frame joint that could be released in a matter of seconds.

Forty years ago, in November 1962, the Moulton was launched, and saved the British cycle industry, whose sales had been plummeting for years. Although most Moultons were not portables, the Stowaway models were and proved a milestone in portable cycle design. Before the Stowaway, portable cycles only occasionally came onto the UK market and there had never been a successful small-wheeled portable. Since the Stowaway, there have always been small-wheeled portables on sale in the UK.Through licensing deals, the Moulton Stowaway was sold by Huffman in the USA, Raleigh in South Africa, Malvern Star in Australia and Jonas Oglaend in Norway. Alex Moulton worked with the Dunlop tyre and rim company, pioneering the adaptation and development of existing juvenile wheel formats (most notably the traditional 16×13/8″ British format) for adult use, using specially made rims and tyres.This ISO 349mm size went on to be used by Bickerton, Brompton, Airframe, Micro and others, and remains a key tyre size today.You can now buy high performance 16″ tyres from Primo, Schwalbe and Brompton – before the Moulton, all you could buy in this size were tyres designed for use on toy bicycles.

Forty years ago, in November 1962, the Moulton was launched, and saved the British cycle industry, whose sales had been plummeting for years. Although most Moultons were not portables, the Stowaway models were and proved a milestone in portable cycle design. Before the Stowaway, portable cycles only occasionally came onto the UK market and there had never been a successful small-wheeled portable. Since the Stowaway, there have always been small-wheeled portables on sale in the UK.Through licensing deals, the Moulton Stowaway was sold by Huffman in the USA, Raleigh in South Africa, Malvern Star in Australia and Jonas Oglaend in Norway. Alex Moulton worked with the Dunlop tyre and rim company, pioneering the adaptation and development of existing juvenile wheel formats (most notably the traditional 16×13/8″ British format) for adult use, using specially made rims and tyres.This ISO 349mm size went on to be used by Bickerton, Brompton, Airframe, Micro and others, and remains a key tyre size today.You can now buy high performance 16″ tyres from Primo, Schwalbe and Brompton – before the Moulton, all you could buy in this size were tyres designed for use on toy bicycles.

Moulton, whose design had been dropped by Raleigh shortly before they were due to mass-produce it, rapidly became the second biggest single-brand cycle maker in the UK. Competitors fought back with rival small-wheelers but could not cost-effectively circumvent Moulton’s patents to produce a bike with the key combination of 16″ high- pressure narrow- section tyres and dual suspension. So most adopted a compromise based on 20″ wheels, sometimes with semi-balloon tyres.

The Dawes Kingpin range was one of the first of these and included a separable model and a folder.The separable was soon dropped, but the folder remained in production for almost 25 years – the longest run of any British small-wheeled folder thus far. (Although Brompton look set to eclipse this record in the not too distant future.)

…The Stowaway… proved a milestone in portable cycle design.

The Raleigh RSW Compact - it seemed to get bigger when folded...

While Raleigh tried to negotiate back the production rights to the Moulton, they competed with its inventor by launching the infamous but commercially successful RSW16 small-wheeler range. This used 2″ wide 16″ diameter balloon tyres. In 1965, a folding version, the RSW Compact was launched. One of its designers was John Dolphin, who during World War 2 designed the folding Welbike moped for the UK Special Operations Executive. (SOE’s mission was to ‘setEurope ablaze’ via bigger when folded… ‘ungentlemanly warfare’.) Certainly the RSW Compact was built like a tank, weighing 7lb more than the Moulton Stowaway. Strangely, it seemed to get bigger when folded. It never sold well and was deleted from the Raleigh range in 1968.

By that time, Raleigh had bought the original Moulton bicycle company.The greatest result of the ensuing Moulton-Raleigh collaboration was the Moulton Mk3.This was similar to the earlier Moultons but with stronger, triangulated rear suspension. It was not sold in portable form but in 1969, Alex Moulton made a few Stowaway versions based on Mk3 prototypes. One of these, known as the Moulton Marathon, was specially built for Colin Martin who in 1970 rode it from England to Australia. He was probably the first cyclist to complete a major intercontinental ride on a portable cycle.

Photos and illustrations courtesy of Tony Hadland, Nigel Sadler, Harlow Cycle Museum Part 2 follows in A to B 34. For a more comprehensive review, read the book ‘It’s in the bag!’ by Tony Hadland and John Pinkerton, and its online supplement by Mike Hessey (www.hadland.net)

![]()